The brand-new iPhone 17 Pro’s anodized aluminum casing is beautiful—until it comes into contact with your keys or loose change in your pocket. That’s right, reviewers are already calling it “Scratchgate.”

For this teardown, we delved into the reasons behind “Scratchgate,” examining the phone under our Evident DSX2000 microscope and enlisting the help of materials scientists for some scratch testing.

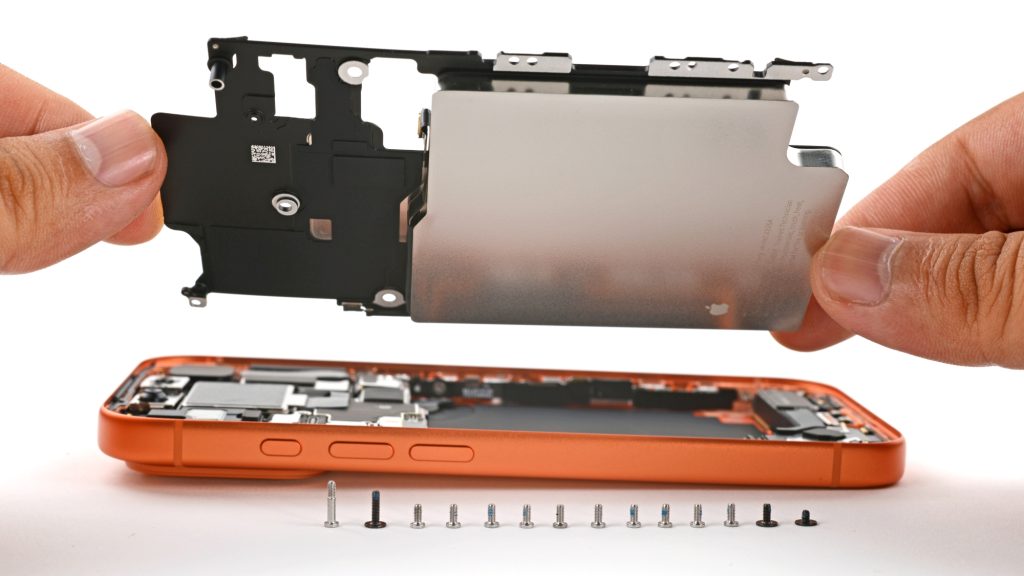

Admittedly, we’re not a professional durability testing facility. But don’t worry, this phone has plenty of interesting repair features: a unique screw-secured battery, a vapor chamber for cooling, and Torx Plus screws—three things never before seen in any iPhone.

While the iPhone 17 Pro lacks some of the repairability features we loved in the iPhone Air teardown we did last weekend, Apple’s redesigned internal structure brings the Pro’s overall repairability score roughly in line with the Air. It’s slightly more difficult to repair than the Air, but the difference is small, so it also earns a repairability score of 7 out of 10. Why? Let us explain.

What exactly is anodizing?

Anodizing is an electrolytic process that forms a protective oxide layer on the surface of a metal. Simply put, it involves slightly corroding the metal surface, and the resulting oxide layer then protects the underlying metal. It’s also widely used to add color to metals, such as the vibrant Starry Sky Orange color of the iPhone 17 Pro. The oxide layer is typically formed by immersing the component in an electrolyte solution and applying an electric current.

Two years ago, we explored this process in detail when we disassembled the M3 MacBook Pro. The controlled corrosion gradually eroded the surface, ultimately creating a matte, deep space black finish. Now, we see the same uneven surface on the iPhone 17 Pro, only this time with added orange dye.

Not all metals can be anodized, but titanium and aluminum can. In fact, one of our engineers anodized a titanium iPhone 15 Pro last year.

Marginal issues

So, is the problem that the phone’s material is aluminum instead of titanium? Titanium oxide is slightly harder than aluminum oxide, but this difference isn’t enough to explain the peeling we’re seeing.

The problem lies in the phone’s shape. Specifically, it’s the sharp edges of the camera bump where the anodized coating doesn’t adhere as evenly as on other parts of the phone.

“Even thickening the oxide layer to reinforce the edges would only result in the same outcome, or even worse,” a thin oxide layer can deform slightly with the substrate. A thicker oxide layer is more prone to peeling and will take more of the substrate with it when it breaks.”

This is why scratches on the flat parts of the phone don’t expose the shiny metal. The anodized layer breaks at the edges of the camera platform, exposing the aluminum underneath, and this stark contrast makes these scratches much more visible to the naked eye.

Is this just a natural consequence of the anodizing process? “Apple could have avoided this by designing a gentler curve and avoiding relatively sharp corners.”

Sharp corners are inherently fragile and prone to breaking or being chipped off. Think of frosted cookies: your star-shaped cookie can easily lose its points.

Although there have been reports of scratching issues with the iPhone Air and the base model iPhone, we haven’t seen the same damage on these phones. Firstly, the glass back covers of both phones are harder than a Mohs hardness level 4 scratching tool.

We know that the iPhone Air’s Ceramic Shield panel 2 is unlikely to show the same scratches. Apple reported to the EU that its Mohs hardness is 5. But for comparison, we still conducted the same test. Even with firm pressure applied to the edges of the camera panel, no scratches or chips were visible under a microscope.

Good luck replacing the scratched back cover: there’s no dual access point.

Okay, it seems we’re prioritizing durability this time, which is a bit beyond our repair capabilities. However, the scratches on the camera panel have also presented some repair challenges. Because Apple has completely redesigned this phone, there isn’t a full-coverage replacement back cover available if you want to replace the scratched panel.

We’ve always appreciated Apple’s dual-entry iPhone design, introduced last year across its entire product line, which allows users to access the phone’s internals from either side for repairs. In these phones, most components can be replaced from beneath the back cover without requiring technicians to remove the fragile and expensive display. We particularly liked this design on the iPhone Air.

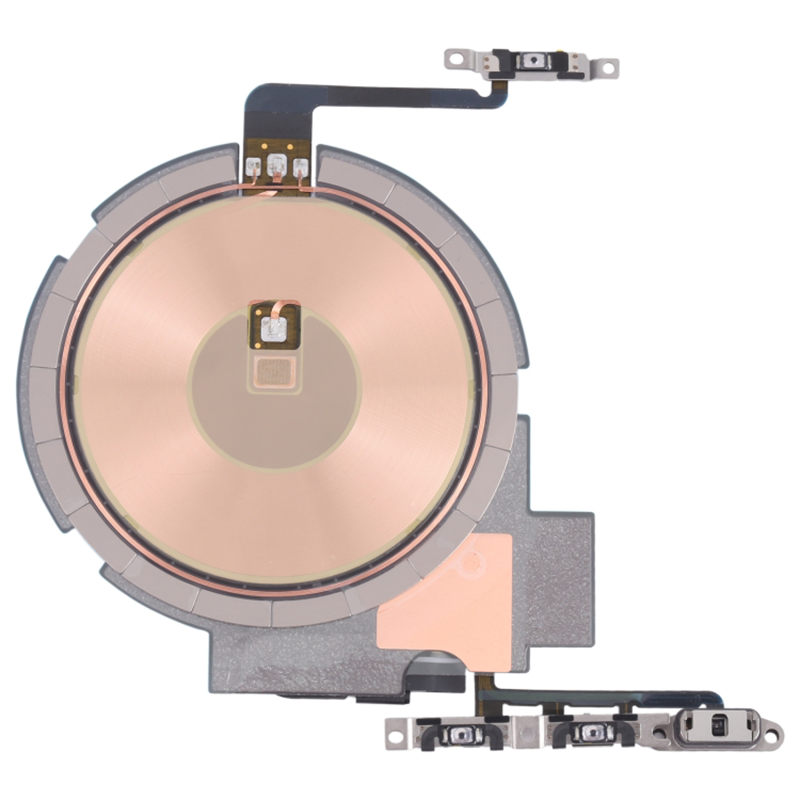

That’s gone now. (Boo, hiss.) Instead, this phone has a small back cover, separate from the camera platform, and only provides access to the wireless charging components, reminiscent of the almost inaccessible screws on the back of the Apple Watch Ultra.

But some repairability wins, at least on paper, help to compensate for this drawback.

How many Apple engineers are needed to install an Apple battery?

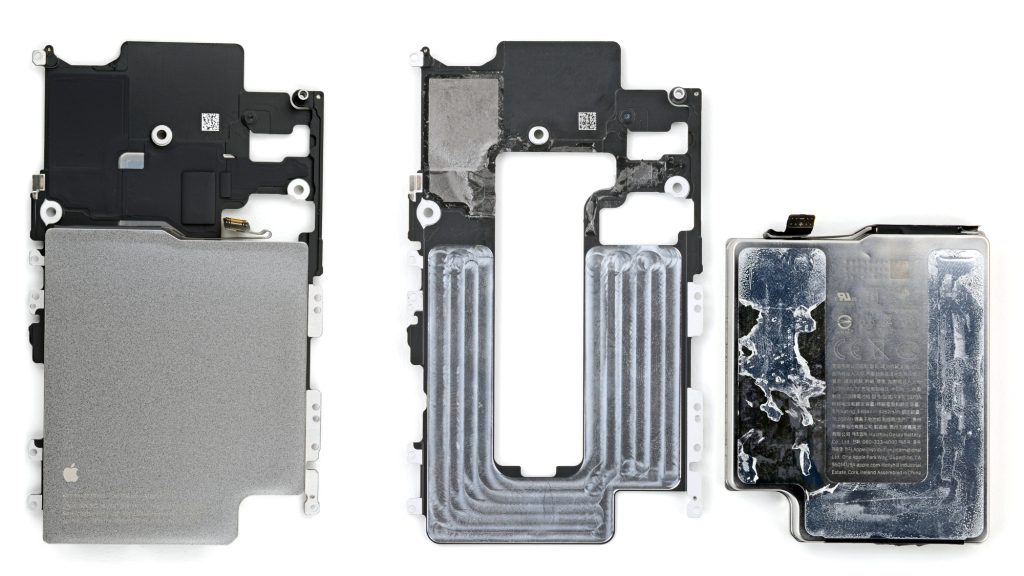

The iPhone’s battery features a screw-secured bracket for the first time: this is the first new feature. Fourteen tiny Torx Plus screws hold it firmly in place. Unscrewing all of these screws is a bit of a hassle, and we’re internally speculating about their purpose and why they’re Torx Plus screws (a cool new type of screw that we wrote a dedicated in-depth blog post about this summer). Is it because of extremely tight manufacturing tolerances that require compressing the battery assembly by a few micrometers? Or is it to ensure better contact between the large metal heatsink of the battery and the heat spreader?

Whatever the reason, we’ve always believed that a screw-secured battery that meets modern design standards is entirely possible, and now we have the evidence. If Apple sold the battery pre-installed in this tray, most users wouldn’t even need to bother with adhesives. Ideally, a screw-secured battery means no dangerous prying, no chemicals, and no need for replacement adhesive.

Apple retained its thermal adhesive, bonding the battery to the tray—so we can still apply 12 volts and watch the adhesive dissolve. After removing the battery, the tray is spotlessly clean. Compared to Samsung’s design of gluing the battery to the screen, this is simply ideal.

A calmer approach

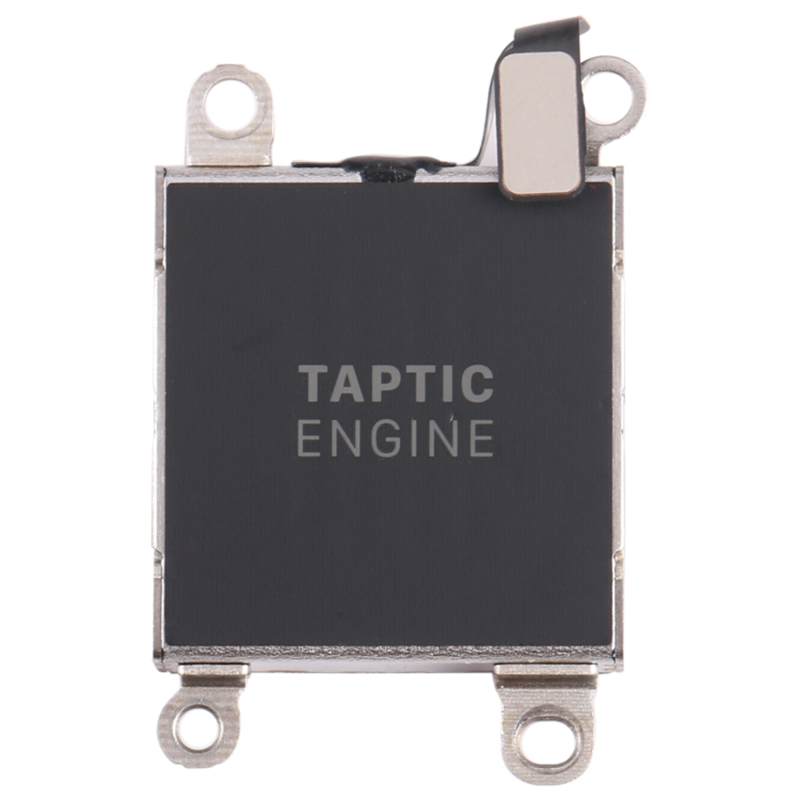

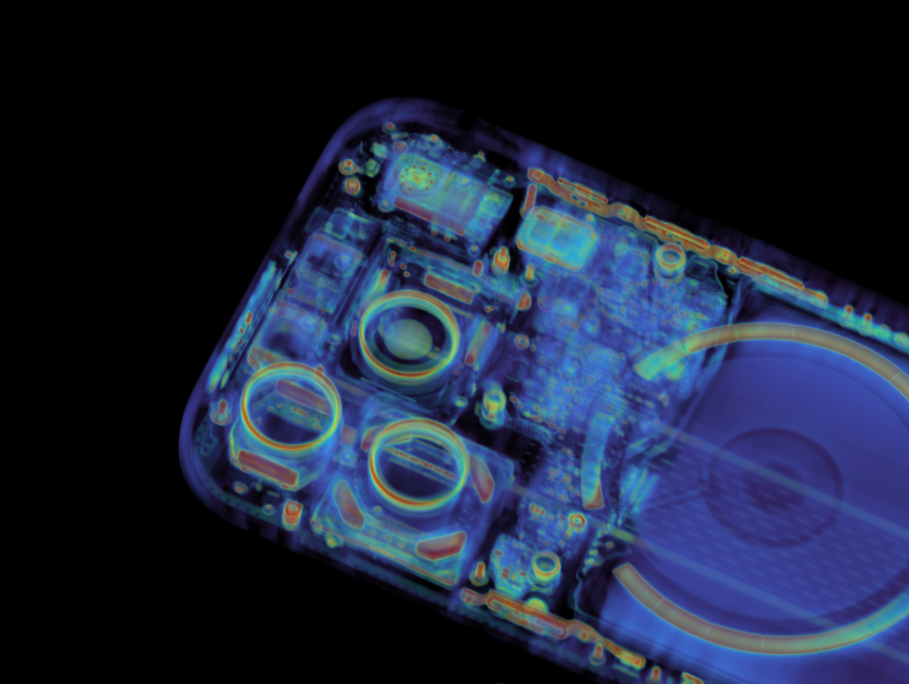

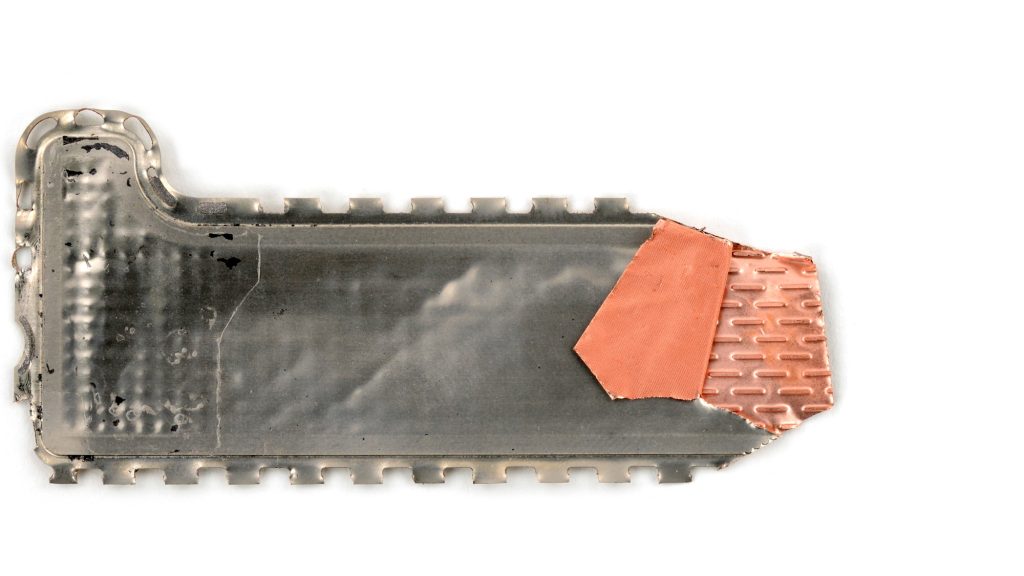

Hidden beneath the tray is another innovative feature of the iPhone: a vapor chamber. If you’ve ever noticed your phone slowing down after prolonged gaming sessions, you’ll understand how important this is. Overheating is harmful to phones; and liquid cooling is an excellent solution.

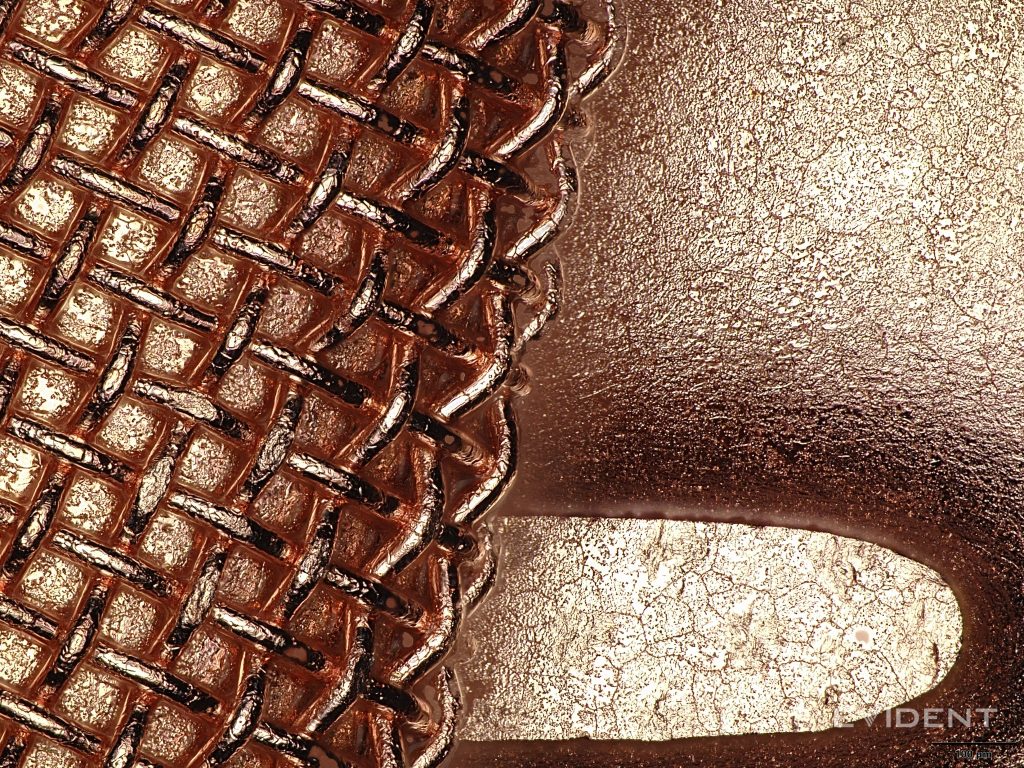

Apple isn’t the first company to introduce this technology (Samsung has been doing it for a while), and the system is surprisingly simple, basically a small copper enclosure that dissipates heat through water absorption. We prefer Apple’s design—its vapor chamber is modular, unlike Samsung’s, which is permanently attached to the device.

This vapor chamber transfers heat from the A19 Pro chip to a water-filled copper mesh, which constantly boils, evaporates, and condenses, creating a continuous cycle. This cycle draws heat away from the processor and transfers it to the phone’s casing. Now that the casing material has been changed to aluminum alloy, our thermal tests show that the iPhone 16 Pro Max starts throttling at an external temperature of 37.8°C (100°F), while the iPhone 17 Pro can stably maintain a temperature of 34.8°C (94.6°F). This might seem insignificant, but for anyone who needs to edit videos or process graphics, this is a significant advantage.

Under a microscope, the heat spreader looks almost like a decorative piece, composed of a grid and copper grooves that help condense the vapor into liquid. Both aesthetically pleasing and functional, it has now become an iconic Apple design.

Camera, connectors, and too many screws.

Fortunately, the modularity of other components is also quite good, including the camera.

This year, the Pro’s three rear cameras all use 48-megapixel Fusion sensors, with vertically arranged photodiodes delivering richer colors and clearer low-light shots. Combined with the A19 Pro chip, this is a significant upgrade for photography enthusiasts. More importantly, these cameras are easily replaceable.

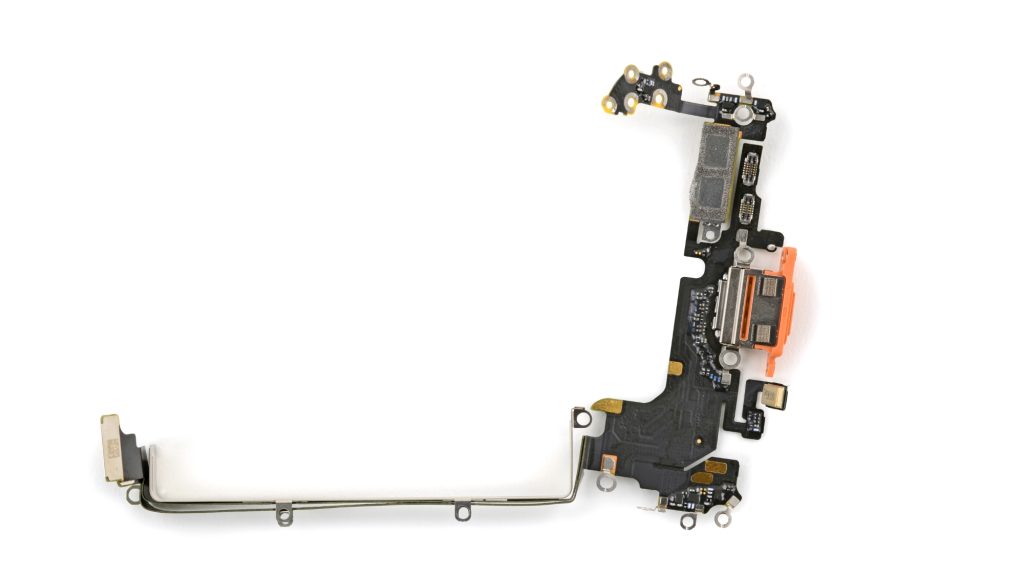

However, if you want to replace the charging port or speakers, be prepared with your screwdriver set. Apple has gone all out on screw types this year. This phone has five types of screws: tri-point screws, Phillips head screws, and plunger screws, with pentalobe screws at the bottom, and Torx Plus screws around the battery and rear camera.

We think screws are better than glue. But we don’t like having to repeatedly switch screwdrivers during repairs. The most elegant repairable designs simplify fastener complexity. Every tool change slows you down. For novice repair technicians, or anyone easily distracted, using the wrong screwdriver bit from the start makes stripping screws more likely. Not to mention the hassle of keeping track of all of them on your workbench.

This thing also has a lot of screws; just replacing the USB-C port requires dozens of screws (it’s maddening!).

So, how should reparability be defined?

The iPhone 17 Pro has received mixed reviews. The screw-secured battery design improves repairability, although we are unsure whether Apple will sell the battery separately, together with the battery tray, or both. The electrically insulating adhesive and metal protective casing make the battery more durable, preventing punctures even if someone tries to pry it open. However, the removal of the dual-opening design means that more repairs will require screen removal, and replacing the USB-C port is also slightly more complicated.

Overall, this phone’s repairability is only slightly inferior to the iPhone Air. Apple provided repair manuals from the product’s launch, and users can find the necessary parts on Apple’s self-service repair website, indicating that Apple considered repairability from the design stage.